Forty-five years ago, cattleman Charles Stevens was asked by the Hardee County Commission to work with a regional planning council on preserving 35,000 acres of county land to keep it from being developed. Stevens, like other ranchers in the county, pushed back. They didn’t believe their old prairie lands and floodplain would ever be desirable for new houses and shopping centers. The County eventually set aside about 2,000 acres.

“If we would have known then what we know now, we would’ve been a lot more receptive to conservation,” Stevens said. “There’s a huge influx of people here now, and they’re subdividing land into 5,10, and 40-acre blocks to put ranchettes on it.”

Stevens raises cattle and citrus on property that sits on a floodplain of Oak Creek, which flows into Charlie Creek, a tributary of the Peace River. The challenges to succeed in farming are numerous, whether it’s from the looming threat of development, or citrus canker and greening, hurricanes, or heat stress to cattle. Chief among those threats is the conversion of land to more intensive land uses.

“A young person can’t even buy land now to raise cattle,” Stevens said. “It’s just too expensive because of everybody else buying it to develop, and it drives up the price. People are offering an enormous amount of money to buy our pasture land.”

Stevens said he hopes to stay in both the cattle and citrus business and pass it down to his children and grandchildren. His daughter and son-in-law are already heavily involved in the operation, which is why Stevens got interested in conservation.

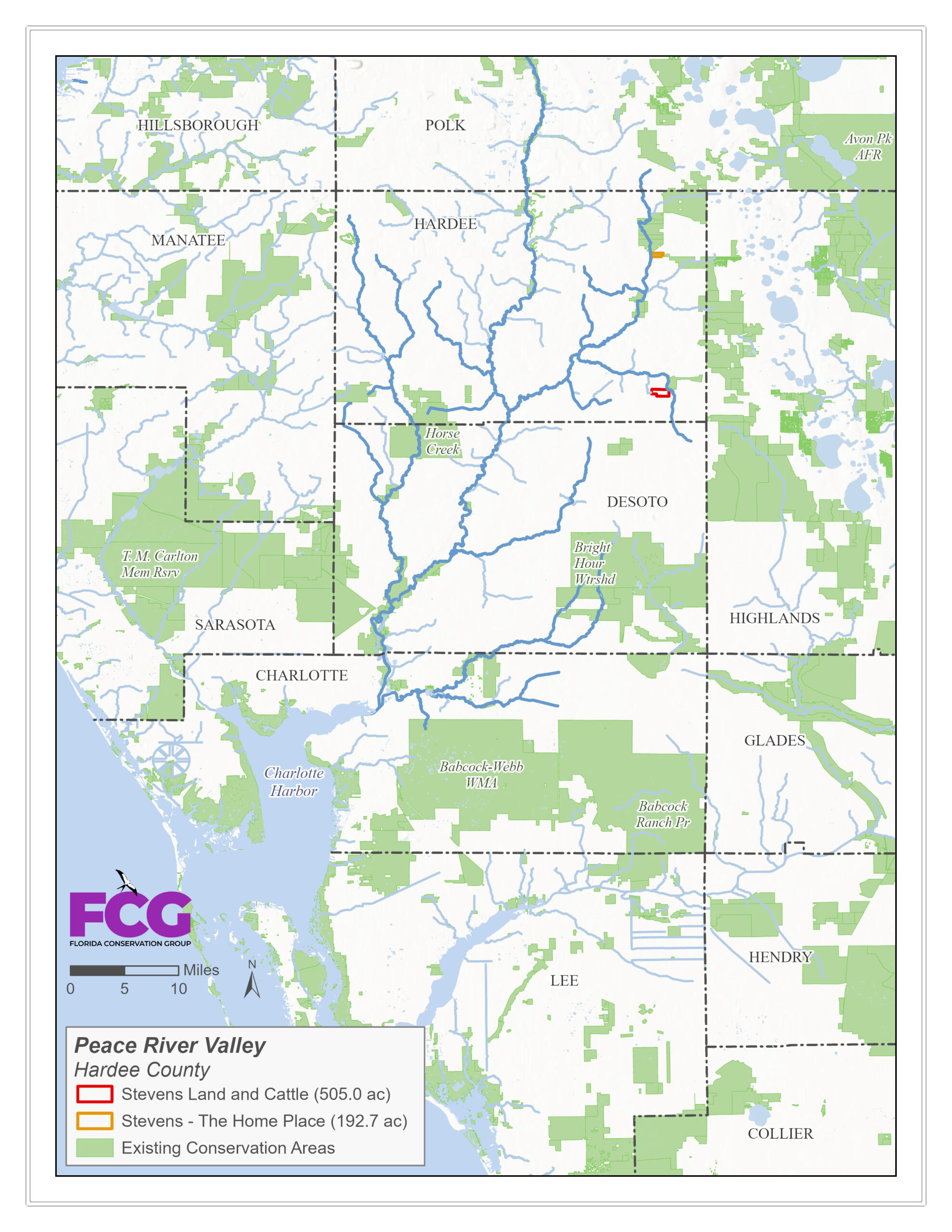

He is in the process of preserving just over 700 acres of his operation in the Peace River Valley into conservation easements through the state. Stevens just closed on his Florida Forever project of around 200 acres and has another 505 acres set to be preserved through the Rural and Family Lands Protection Program.

The 202-acre Stevens Home Place is on Charlie Creek, which is one of most significant tributaries to the Peace River, and in a high priority wildlife corridor. Stevens runs a cow/calf operation there in a natural Old Florida setting. It will now be preserved that way forever.

“I’d never thought much about easements, but a neighbor sold an easement on Old Town Creek, and it got me interested,” Stevens said. “When I’m dead and gone, I don’t want my children faced with the same pressure to convert this land as I’ve had. My grandchildren seem to enjoy this way of life too, so I want it to be there for them.”

The land is well worth preserving. Stevens Land and Cattle is about 505 acres of cattle and citrus that sits on Oak Creek. It is part of the Upper Oak Creek sub basin and a tributary of Charlie Creek and the Peace River drainage basin that flows into the river and Charlotte Harbor.

Conservation of land in the valley will help ensure the quality of water flowing into the Peace River, an important drinking water source for residents of Hardee, Desoto, and Charlotte counties. The protection of Stevens’ land will also regulate, protect, and enhance water flowing into the Gulf, whose outstanding waters are dependent on the maintenance of healthy regional watersheds including the Peace River Watershed.

Hardee County holds among the least amount of conservation lands in the state. But maintaining the continuity of a landscape like Stevens’ in an agriculturally important rural county is pivotal. The ranch sits at the center of a gap of conservation lands between another easement and Highland Hammocks State Park to the east, and Horse Creek Ranch to the west. Encroaching development is a serious threat to Stevens’ property and the immediate region.

Stevens said he hopes the state continues to fund the land conservation programs so other ranchers and farmers can stay in agriculture. The programs conserve lands and ecosystems, but they also both allow cattlemen and citrus growers to continue their operations and pass them down to family.

“I’m glad the state has stepped up to the plate to make these programs possible,” Stevens said. “Cattle is what I know best and I’m not ready to throw in the towel yet. There are a lot of folks like me out here who could use these programs to stay in business.”